The early days

The earliest arechaeological finds and the information available in archival documents agree on setting the start of the ceramic production in Albisola around the last quarter of the 15th century, favoured by the presence of red clay deposits and of white earth quarries, found in various places of the plain and on the hillsides, of woods in nearby valleys and by the location along the beach, which facilitated the loading of finished products, also offering large spaces for drying the molded items.

Since the very beginning the ceramic production was divided in two main types: engobed and graffitoed earthenware and majolica. In the former, processing is divided into two stages: the object is molded, covered with engobe, obtained by dissolving white earth in water and graffitoed with a fine point, fired and then covered with glaze or varnish (polychrome types having been previously decorated with spotsof color) and fired a second time.

In majolicas, the earthenware object is fired a first time, then dipped in a bath of glaze, or majolica, made opaque by the presence of tin. Brush decorations are made on this coating, then the object is fired a second time.

The 15th and 16th century

By the end of the 15th century, an abundant production of engobed and monochrome graffitied earthenware is known: these are yellow-brown or green plates and bowls, often decorated with a cross motif and a few specimens with green and brown flecks under yellow paint. The production of majolica is not yet well-defined in this early period.

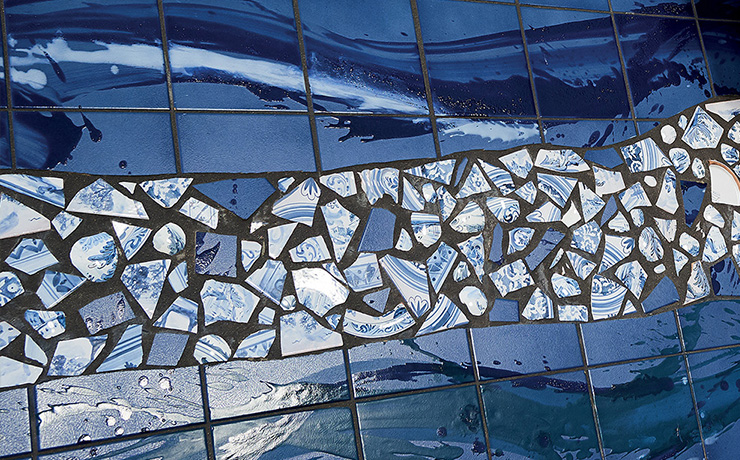

Very early, at the start of the 16th century, began the production of laggioni, or wall or floor tiles, covered with brightly colored glaze, according to designs derived from Islamic art or Renaissance taste. In Albisola there is an important work in majolica tiles, signed by Giovanni Giacomo Sciaccarama and dated 1554, which reproduces the text of a resolution of the administrators of the ancient Hospital of San Nicolò, in white on blue tiles. Many other laggioni with different designs are displayed in the Manlio Trucco Ceramics Museum. Also typical of the 16th century is the production of majolica covered with berettino glaze, bright blue in color, and decorated in a darker shade of blue. Another widespread type is white glaze decorated with blue stylized plant motifs. A few recent archaeological finds allow us to speculate on the existence of production in the compendiary style: that is, with a white ground with sparse blue or polychrome decorations, an imitation of those produced in Faenza.

The earliest arechaeological finds and the information available in archival documents agree on setting the start of the ceramic production in Albisola around the last quarter of the 15th century, favoured by the presence of red clay deposits and of white earth quarries, found in various places of the plain and on the hillsides, of woods in nearby valleys and by the location along the beach, which facilitated the loading of finished products, also offering large spaces for drying the molded items.

Since the very beginning the ceramic production was divided in two main types: engobed and graffitoed earthenware and majolica. In the former, processing is divided into two stages: the object is molded, covered with engobe, obtained by dissolving white earth in water and graffitoed with a fine point, fired and then covered with glaze or varnish (polychrome types having been previously decorated with spotsof color) and fired a second time.

In majolicas, the earthenware object is fired a first time, then dipped in a bath of glaze, or majolica, made opaque by the presence of tin. Brush decorations are made on this coating, then the object is fired a second time.

The 15th and 16th century

By the end of the 15th century, an abundant production of engobed and monochrome graffitied earthenware is known: these are yellow-brown or green plates and bowls, often decorated with a cross motif and a few specimens with green and brown flecks under yellow paint. The production of majolica is not yet well-defined in this early period.

Very early, at the start of the 16th century, began the production of laggioni, or wall or floor tiles, covered with brightly colored glaze, according to designs derived from Islamic art or Renaissance taste. In Albisola there is an important work in majolica tiles, signed by Giovanni Giacomo Sciaccarama and dated 1554, which reproduces the text of a resolution of the administrators of the ancient Hospital of San Nicolò, in white on blue tiles. Many other laggioni with different designs are displayed in the Manlio Trucco Ceramics Museum. Also typical of the 16th century is the production of majolica covered with berettino glaze, bright blue in color, and decorated in a darker shade of blue. Another widespread type is white glaze decorated with blue stylized plant motifs. A few recent archaeological finds allow us to speculate on the existence of production in the compendiary style: that is, with a white ground with sparse blue or polychrome decorations, an imitation of those produced in Faenza.

The ceramic kilns resulting from the oldest cadastre, dated 1569, are fourteen, of which thirteen are in Albisola Marina and only one in Superiore. In the next cadastre in 1612, a kiln also appears in the hamlet of Capo, and the first color mill, used to grind paints and colors and any other material intended for ceramic factories, appears along the Sansobbia stream in the Ellera area. In 1640-41 there were 23 kilns in Albisola Marina (which in 1615 broke away from Superiore, forming an independent municipality), one in Superiore, one more in Capo, and two color mills in Ellera. We are therefore at a time of great flourishing of production. Evidently pottery decorated in monochrome blue is enjoying great popularity.

The 17th and 18th century

The type of decoration called calligraphic-naturalistic, reproduced in some paintings from the first half of the 17th century, is supposed to have preceded the so-called tapestry and historiated types. One of the most talented painters of the calligraphic tapestry type was Gerolamo Merega (Albisola Superiore, 1636-1679), who in 1676 supplied nearly 500 apothecary jars to the Genoese hospital of Pammatone. Some of these vases are on display at the Trucco Museum. The production of majolica with the various decorations in monochrome blue continued in Albisola until the mid-18th century. In the last period the taste for the intense blue color was waning and the majolica objects were largely white, with blue decorations limited to the edges. The production of polychrome majolica in the new "figure-like" decorations, what is now called the Levantine style must have been scarcer. In Savona, on the other hand, it was precisely in the 18th century that important companies developed and a number of artists, also skilled entrepreneurs, emerged: Giacomo Boselli excelled among them all.

19th century: decline and rebirth

Albisola majolica was in full decline at the beginning of the new century, with nothing more than modest mugs and bowls being made, plain white or bearing the simple so-called "a fioracci" decoration in blue or manganese. Engobed and graffitoed earthenware also continued to be produced by Albisola factories throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, alongside the more refined majolica, for a more modest clientele. Many specimens of the rich terracotta production of the last years of the 17th and early 18th centuries, including, in addition to the conventual graffiti, monochrome or polychrome engobed and graffitied objects, objects covered with marbled engobe, pots, vases and kitchen jars, and containers for on-board use, are on display at the Trucco Museum and come from an excavation carried out in 1983 at the Giacchino kiln in Albisola Superiore.

This entire production began to die out around the third decade of the 19th century to give way to a new type of unsophisticated terracotta, which was very successful and whose origin is unknown. It is what we now call terracotta a taches noires, using a term taken from the Statistics of the Department of Montenotte by Prefect Chabrol de Volvic. It is a new type of terracotta decorated under paint, with stripes drawn freely with a brush soaked in manganese. The lead paint enriched with ironstone takes on a brown coloring, below which the stripes or spots, almost black, stand out with a pleasing effect. This new product really boomed in Albisola: the kilns multiplied, especially in the hamlet of Capo, where they reached the number of fourteen, but they were mostly bought or built by families of the Genoese nobility, such as Della Rovere and especially Balbi.

Production reaches 25 million pieces per year. It is a truly popular, inexpensive product that is even exported to America. Only the imposition of heavy duties by France and Spain manages to cause a crisis in production, which heavily involves, in the early 19th century, the Albisolese community. The manufacturers are forced to self-limit through an agreement that establishes the maximum number of firings per year for each kiln, almost halving the production.

In the early 19th century there is a gradual increase in the production of so-called black earthenware, that is, terracotta painted in manganese brown, which soon supplants terracotta decorated with taches noires. But for black earthenware, too, despite regulations and agreements among potters, the crisis hits, around the middle of the century. This time Albisolese manufacturers find an outlet in a new field, the production of fire pots. Such production is favored particularly in the hamlet of Capo, thanks to the construction of the railway line and station. After a period of great success at the turn of the century, it will die out in the 1950s.

Also in the vein of folk production, there are the nativity scene figurines, made at home in the evening, using old molds, with a little soil brought in by factory workers. Most of the figurines were sold on December 13 in Savona at the traditional Santa Lucia fair.

The 17th and 18th century

The type of decoration called calligraphic-naturalistic, reproduced in some paintings from the first half of the 17th century, is supposed to have preceded the so-called tapestry and historiated types. One of the most talented painters of the calligraphic tapestry type was Gerolamo Merega (Albisola Superiore, 1636-1679), who in 1676 supplied nearly 500 apothecary jars to the Genoese hospital of Pammatone. Some of these vases are on display at the Trucco Museum. The production of majolica with the various decorations in monochrome blue continued in Albisola until the mid-18th century. In the last period the taste for the intense blue color was waning and the majolica objects were largely white, with blue decorations limited to the edges. The production of polychrome majolica in the new "figure-like" decorations, what is now called the Levantine style must have been scarcer. In Savona, on the other hand, it was precisely in the 18th century that important companies developed and a number of artists, also skilled entrepreneurs, emerged: Giacomo Boselli excelled among them all.

19th century: decline and rebirth

Albisola majolica was in full decline at the beginning of the new century, with nothing more than modest mugs and bowls being made, plain white or bearing the simple so-called "a fioracci" decoration in blue or manganese. Engobed and graffitoed earthenware also continued to be produced by Albisola factories throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, alongside the more refined majolica, for a more modest clientele. Many specimens of the rich terracotta production of the last years of the 17th and early 18th centuries, including, in addition to the conventual graffiti, monochrome or polychrome engobed and graffitied objects, objects covered with marbled engobe, pots, vases and kitchen jars, and containers for on-board use, are on display at the Trucco Museum and come from an excavation carried out in 1983 at the Giacchino kiln in Albisola Superiore.

This entire production began to die out around the third decade of the 19th century to give way to a new type of unsophisticated terracotta, which was very successful and whose origin is unknown. It is what we now call terracotta a taches noires, using a term taken from the Statistics of the Department of Montenotte by Prefect Chabrol de Volvic. It is a new type of terracotta decorated under paint, with stripes drawn freely with a brush soaked in manganese. The lead paint enriched with ironstone takes on a brown coloring, below which the stripes or spots, almost black, stand out with a pleasing effect. This new product really boomed in Albisola: the kilns multiplied, especially in the hamlet of Capo, where they reached the number of fourteen, but they were mostly bought or built by families of the Genoese nobility, such as Della Rovere and especially Balbi.

Production reaches 25 million pieces per year. It is a truly popular, inexpensive product that is even exported to America. Only the imposition of heavy duties by France and Spain manages to cause a crisis in production, which heavily involves, in the early 19th century, the Albisolese community. The manufacturers are forced to self-limit through an agreement that establishes the maximum number of firings per year for each kiln, almost halving the production.

In the early 19th century there is a gradual increase in the production of so-called black earthenware, that is, terracotta painted in manganese brown, which soon supplants terracotta decorated with taches noires. But for black earthenware, too, despite regulations and agreements among potters, the crisis hits, around the middle of the century. This time Albisolese manufacturers find an outlet in a new field, the production of fire pots. Such production is favored particularly in the hamlet of Capo, thanks to the construction of the railway line and station. After a period of great success at the turn of the century, it will die out in the 1950s.

Also in the vein of folk production, there are the nativity scene figurines, made at home in the evening, using old molds, with a little soil brought in by factory workers. Most of the figurines were sold on December 13 in Savona at the traditional Santa Lucia fair.

The 20th century: the artistic breakthrough

Majolica production, interrupted at the beginning of the 19th century, resumed in Albisola at the turn of the century, thanks to some new factories. The Poggi firm had begun in 1862, producing white dishes in the Mondovì manner in a new, round-shaped kiln. With Nicolò Poggi the adventure in the field of artistic ceramics began. Almost simultaneously, Giuseppe Piccone entered the market. After a decade, in 1903, Giuseppe Mazzotti, known as Bausin, joined too.

The season of futurism mark a time of great development in Albisola ceramic art, thanks to well-known artists working and firing in local kilns, attracted by the personality of Tullio Mazzotti or Tullio d'Albisola. In this period it’s remarkable the presence, at Manlio Trucco's kiln, of Arturo Martini, the great sculptor from Treviso who would settle in nearby Vado Ligure. The ceramics of many artists clearly denote the influence of his work. Even after World War II, Tullio d'Albisola is the hub around which the greatest personalities of the national and international art scene gravitate. Albisola is recognized as the capital of ceramics. The Incontri Internazionali della Ceramica (International Meetings of Ceramics) are organized, and alongside them various types of exhibitions, competitions and prizes.